I May Be Wild but I m Not What Was That Third Thing Again

Ecology and Management of Wild Pigs

Table of Contents

- Introduction

- Population

- Predation

- Reproduction

- Nutrition

- Harm

- Affliction

- Control

- Hunting

- Compensation

- Resource

Wild Pigs

Environmental and Management of Wild Pigs

John C. Kinsey, CWB. 2020.

This web page is intended to serve equally an informative site to provide the most current data available to the public as well as natural resource managers on wild pig environmental and management. Wild hog control in Texas and throughout the U.s. is a collaborative effort between many governmental and private entities with expertise in specific areas of wild hog control, management, and damage mitigation. Thus, we will provide some links to informative resource from those entities based on their area of expertise.

Because specifics about wild hog behavior, life history, and ecology vary throughout their range and because they are a relatively understudied species, this web page is not intended to be Texas specific and volition provide data from beyond the continental United States. Notwithstanding, it will offering Texas specific examples where possible and appropriate.

Introduction to North America

Pigs (Sus scrofa) are non native to Due north America (i, ii). The species was first introduced to the W Indies by Christopher Columbus in 1493 and so to the continental The states by Castilian explorer Hernando de Soto in 1539 when he landed at the Florida declension (3, 4). Domestic pigs were ofttimes carried on these excursions as a sustainable, depression maintenance source of food. Equally explorers moved across the continent those domestic pigs would often be left behind, establishing the showtime populations of feral pigs in Northward America (5). The term feral refers to a domestic fauna that has gone wild. Post-obit these initial introductions, European settlers and Native Americans implemented gratuitous-ranging farming practices of domestic pigs that promoted the spread of feral hog populations (ane, 6). Free-range farming methods were still practiced in some states through the 1950s (1). In addition to these feral pigs, Eurasian wild boar have been imported and released as an exotic game species for recreational hunting purposes across the United States since the early on 1900s (1). Today's free-range pig population in the United states is fabricated up of feral pigs, Eurasian wild boar, and hybrid populations resulting from cantankerous-breeding of Eurasian wild boar and feral pigs (4). Though at that place are morphological differences amongst the three, they are all referred to by the same scientific name and all recognized as exotic invasive species in the United States. Thus, for the purposes of this certificate all iii subpopulations will be treated every bit one and will hereafter be referred to as wild pigs (1, 7, 8).

Population Trends

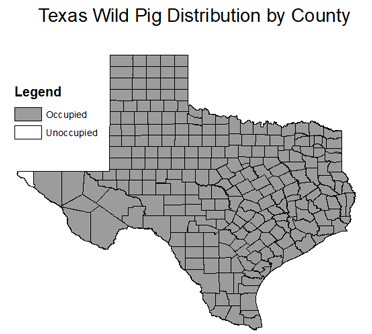

Wild pigs are now the United states of america' most abundant costless-ranging introduced ungulate (nine). The term ungulate refers to animals which have hooves. From 1982 to 2016, the wild pig population in the U.s.a. increased from 2.4 million to an estimated 6.9 million, with ii.6 million estimated to be residing in Texas alone (10, 11). The population in the United States continues to grow quickly due to their loftier reproduction rate, generalist nutrition, and lack of natural predators (2, nine). Wild pigs have expanded their range in the U.s.a. from eighteen States in 1982 to 35 States in 2016 (2). It was recently estimated that the charge per unit of northward range expansion by wild pigs accelerated from approximately 4 miles to seven.8 miles per twelvemonth from 1982 to 2012 (12). This rapid range expansion can exist attributed to an estimated 18-21% annual population growth and an ability to thrive across various environments, however, one of the leading causes is the human-mediated transportation of wild pigs for hunting purposes (thirteen-15).

Predation

In Europe and Asia, predation by natural predators can account for up to 25% of almanac mortality at the population level (16). In the U.s.a., however, humans are the near significant predator of wild pigs (5). Though predators such every bit coyotes (Canis latrans), bobcats (Lynx rufus), and golden eagles (Aquila chrysaetos) may opportunistically prey upon immature wild pigs; it is but where wild pigs exist with American alligators (Alligator mississippiensis), mountain lions (Puma concolor), and blackness bears (Ursus americanus) that any frequent intentional predation of the species may occur (17-xix). Fifty-fifty where this type of predation does occur, it plays a minor office in wild pig mortality (5).

Reproduction

The age at which reproductive maturity is reached is highly variable amongst populations of wild pigs (20). Males accept been documented to accomplish sexual maturity by five months of age and have been observed attempting to breed at half dozen months. However, breeding success is strongly correlated with size (20, 21). Thus, males are not typically successful in convenance until 12 to 18 months of historic period (eighteen). Reproductive maturity has been documented in female person wild pigs every bit early on as three months of age, though successful beginning breeding is mostly reported to occur between the ages of 6 and ten months (eighteen, 22). Equally with males, female reproductive maturity is as well correlated with size. Researchers have found that females did not achieve reproductive maturity until they reached approximately 100-140 lbs (22).

Pigs have the highest reproductive rate of any ungulate; only like reproductive maturity, it is highly variable amongst populations (23-25). Females (sows) have multiple estrous cycles annually and can breed throughout the twelvemonth with an average litter size of 4-6 young per litter (5). The average gestation period for a sow is approximately 115 days and they can breed again within a week of weaning their young, which tin occur approximately ane calendar month after birth (26, 27). Though information technology is a physiological possibility for a sow to have three litters in approximately 14 months (28), researchers found that in southern Texas adult and sub-adult sows averaged 1.57 and 0.85 litters per year, respectively (25). Birthing events can occur every month of the year, though virtually wild pig populations showroom prominent peaks in birthing events that correlate with fodder availability (25, 29) with peaks generally occurring in the winter and spring months (thirty). In areas where provender is not a limiting gene, such as lands in cultivation or where supplemental feeding for wild fauna is common practice, reproduction rates tin can be higher than average (31).

Diet

Wild pigs are omnivores, generally categorized every bit opportunistic feeders, and typically consume betwixt 3% and five% of their full body mass daily (32). They exhibit a generalist nutrition consuming a diversity of nutrient sources which allows them to thrive across a wide range of environments (1, x, 33). Throughout their range their nutrition is generally herbivorous, shifting seasonally and regionally among grasses, mast, shoots, roots, tubers, forbs, and cacti equally resource availability changes (iv, 30, 34). When available, wild pigs will select for agricultural crops, frequently making up over 50% of the vegetative portion of their diets and causing pregnant damage to agricultural fields (35, 36). Invertebrates are oftentimes consumed while foraging for vegetation throughout the yr including insects, annelids, crustaceans, gastropods, and nematodes (37). Studies take shown that, in some cases, invertebrates are highly selected for and seasonally brand up over 50% of wild pig diets (38, 39). Wild pigs will too eat tissues of vertebrate species through scavenging and straight predation (37, twoscore, 41). Studies have documented intentional predation of various vertebrate species by wild pigs including juvenile domestic livestock, white-tailed deer (Odocoileus virginianus) fawns, ground nesting bird nests (Galliform sp.), and various species of reptiles and amphibians (41-43, 97, 98).

Damage

Wild pigs take been listed as ane of the acme 100 worst exotic invasive species in the world (44). In 2007, researchers estimated that each wild grunter carried an associated (damage plus control) cost of $300 per twelvemonth, and at an estimated 5 one thousand thousand wild pigs in the population at the fourth dimension, Americans spent over $i.5 billion annually in damages and command costs (45). Bold that the cost-per-wild squealer judge has remained abiding, the almanac costs associated with wild pigs in the United States are likely closer to $2.1 billion today (10, 11, 45).

Most damage caused by wild pigs is through either rooting or the direct consumption of plant and animal materials (5). Rooting is the machinery past which wild pigs unearth roots, tubers, fungi, and burrowing animals (5, 46). They utilize their snouts to dig into the ground and plough over soil in search of food resources, altering the normal chemistry associated with food cycling within the soil. Farther, the mixing of soil horizons that often accompanies rooting by wild pigs has likewise been shown to change vegetative communities, allowing for the establishment and spread of invasive plant species (33). It has been estimated that a single wild pig can significantly disturb approximately 6.5 ft2 in only one minute (47). This large-scale soil disturbance can increase soil erosion rates and have detrimental effects to sensitive ecological areas and critical habitats for species of business (41, 48, 49). When wild pigs root or wallow in wetland or riparian areas, it tends to increase the nutrient concentration and total suspended solids in nearby waters due to erosion (48, l).

Wild pigs also directly contribute fecal coliforms into water sources, increase sedimentation and turbidity, alter pH levels, and reduce oxygen levels (51, 52). Such activities lead to an overall reduction in water quality and deposition of aquatic habitats. Impacts from wild pigs are positively correlated with population density and vary in severity amidst ecosystems. Native habitat degradation as well as loss of biodiversity and ecosystem services acquired by wild pigs are difficult to quantify and impossible to fully assign monetary value. However, monetizing such impairment would undoubtedly increment the estimated costs associated with the species (35).

Economically, wild pigs take the greatest touch on the agricultural manufacture in the United States (two). In 2005, researchers estimated that in a single night, one wild grunter can cause at least $i,000 in damages to agriculture (53). In Texas, a 2006 publication reported that wild pigs caused approximately $52 million in agricultural damage annually (54). More contempo studies published in 2016 and 2019 guess that the annual loss to agriculture in Texas is approximately $118.8 meg (95, 96). Impacts to crops are not limited to direct consumption. Trampling of standing crops and damage to soil from rooting and wallowing activities account for ninety-95% of crop impairment, in some cases (55). Continuing crops are non the but course of agriculture damaged by wild pigs. Wild pigs also crusade damage to hay fields, orchards, farming equipment, and fences.

The human population of the U.s.a. is chop-chop growing, and the majority of that population lives in urban areas. In general, the resulting expansion of urban sprawl has increased human-wild animals interactions (62). That trend along with the contempo population growth and range expansion of wild pigs has resulted in an increase in damage to private belongings and common recreational areas (5). Wild pigs often seek out food and water in residential areas during times of drought which leads to damage of landscaping, fencing, and irrigation systems in residential areas as well as communal areas such as golf game courses and parks (5, 63, 64). In addition, wild hog-vehicle collisions tin result in pregnant belongings damage also as human injury and death (56). Researchers conservatively estimated damages associated with wild sus scrofa-vehicle collisions to exist $36 million annually in the United States alone (67). Because projections show rapid expansion of both man and wild pig populations the frequency of wild grunter-vehicle collisions volition likely increase, too (65). Not only do wild pigs physically damage natural resources and agricultural crops, personal belongings, and equipment, they besides have a loftier potential to transmit various diseases to domestic livestock (56).

Disease

Wild pigs are capable of carrying and transmitting at least 30 bacterial, fungal, and viral diseases which threaten humans, livestock, and wild animals (7, 57). Some of those which can infect humans are brucellosis, leptospirosis, toxoplasmosis, and trichinosis (58). Though disease transmission to humans is a existent business organization, the largest threat from wild sus scrofa diseases is the potential transmission to domestic livestock. Diseases such as swine brucellosis, pseudorabies, classic swine fever, and African swine fever can issue in birth defects and decease of various livestock and wildlife species (seven). Diseases such equally classic swine fever and foot and rima oris affliction have been eradicated from the Usa pork industry and are considered foreign-animal diseases. Wild pigs, however, have the potential to act equally a reservoir for these diseases making it hard or incommunicable to eradicate them once again in areas with infected wild pig populations (59). A scenario where one of these diseases is reintroduced could cause crippling impairment to the United states agricultural industry (vii, 60). One farthermost scenario is the reemergence of human foot and mouth disease in the United States. If this illness were to be reintroduced to the domestic livestock industry, it could cause up to $21 billion in loss of agronomical income and a portion of small-scale farmers to lose their farms (61). For more information on diseases transmissible to humans, domestic animals and wildlife, please come across Diseases of Feral Swine (PDF).

Population Command

Though non-lethal means of reducing impairment from wild pigs is sometimes constructive at pocket-sized scales, the only mode to alleviate broad-spread impacts from wild pigs is to reduce the overall population. Lethal command measures are currently the only effective means of reducing wild pig populations. There are multiple lethal control techniques currently available to land managers and owners in the Us (56). Nevertheless, no single method approaches the scale necessary to accept a significant, long-term effect on wild squealer populations across large tracts of land, and most certainly not at a national scale (68). The virtually popular methods of lethal control currently legal in the United States are trapping and dispatching, ground shooting, and aerial gunning.

Trapping

Dispatching after trapping is the near popular method of lethal command for wild pigs (69). There are a wide range of trap designs for wild pigs, but they generally autumn under ii categories; box traps and corral traps. Box traps vary in design, but are typically enclosed traps that are designed to be easily transportable and set by one person. These types of traps are virtually effective when used to target small groups or single animals that frequently cause holding damage. The minor box traps facilitate transportation from one trap site to some other, but limit the number of animals that can exist caught at one time. If used to target big sounders, those that are not successfully trapped may develop learned behavior which makes them more than difficult to trap in the future (68).

Corral traps are typically much larger semi-permanent structures, though at that place are several portable corral traps commercially available. These traps allow for more animals to be caught at one time which more than effectively reduces populations and increases the cost efficacy of trapping. Studies have found that corral traps provided a capture charge per unit greater than four times that of individual box traps (68). Toll associated with corral trapping accept been shown to vary greatly, ranging from $14.32 to $121 per pig. After the initial buy of either pre-constructed trap or trap building materials, the main contributor to the loftier costs associated with this method is the time it takes to set up and monitor corral traps (68). Researchers have institute that the use of corral traps resulted in the removal of 0.20 and 0.43 wild pigs per man-hour, respectively (lxx, 71). This equates to approximately 2 to 5 hours of work per each wild grunter removed.

Efficacy of trapping whole sounders has increased with recent advances in remote camera engineering science. These movement activated cameras tin can be used to monitor wild hog activity at trap sites with nevertheless photographs or short videos. The most contempo advocacy in remote photographic camera engineering science allows real-time monitoring of wild pig activity on your telephone, tablet, or computer using cellular data. Agreement wild pig behavior at a trap site allows trappers to make more educated decisions on when to set the trap trigger and so that the number of wild pigs caught is maximized. In addition, the same cellular technology that allows for real-fourth dimension camera monitoring has facilitated the advent of remotely triggered trap gates. This allows for trappers to monitor wild grunter activity on a personal device in real time and trigger the trap gate remotely from the same device one time the entire sounder has entered the trap. Though trapping is one of the most effective ways of large-calibration population reduction currently available in the United States, its impacts are often limited by the inability to deploy traps in remote areas difficult to reach by vehicle or boat (68, 72).

For more information on various trap designs, trapping strategies, and proper implementation, please visit the links below:

- Wild Pigs

- Coping with Feral Hogs

- Using Game Cameras for Feral Hogs

Aerial Gunning

Shooting wild pigs while flying in fixed fly or rotary aircrafts is frequently referred to as aeriform gunning. Aerial gunning is a highly effective means of quickly reducing wild pig populations in areas with big expanses of sparse canopy cover and high densities of wild pigs (5, 73, 74). Every bit visibility and population density decrease, however, so does the efficacy of this method in both cost and reduction of populations (56, 74, 75). Thus, this method is most effective in areas with sparse tree canopy and loftier wild hog densities. At that place is also some debate as to whether or not this method alters beliefs in wild pig populations causing them to increase home ranges and acquire to avoid shipping, making them more difficult to find via helicopter (74, 76, 77). In private-country states similar Texas, gaining permission and sufficient acreage from contiguous landowners can be a claiming. Similarly, the high costs associated with aircraft rental and pilots may non be viable for some. Even so, where tree canopy allows, aerial gunning can exist the most effective ways of rapid wild pig population reduction available (56, 72).

For more information on aeriform gunning, please see:

- Aeriform Wildlife Management Permits

- "Costs and effectiveness of damage management of an overabundant species (Sus scrofa) using aeriform gunning PDF".

USDA Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service — Wildlife Services. world wide web.aphis.usda.gov/wildlife_damage/nwrc/publications/

18pubs/rep2018-164.pdf.

Basis Shooting

Basis shooting encompasses several methods, only the most commonly used methods in the United States are running trained tracking dogs, nighttime shooting, and recreational hunting.

Tracking Dogs

The success of removing wild pigs using tracking dogs is dependent on the skill of both the hunter and the dogs being used. I report indicated that dogs could only take hold of 4 pigs per day before getting too tired to chase (78). They too noted that catch success declined as sounder size increased. Thus, hunting wild pigs with dogs is not an effective ways of big-calibration population reduction. However, the use of highly skilled dogs may be necessary to remove wild pigs which avert other control techniques as trained dogs can track individuals through dense vegetation and across rugged terrain (5, 72).

Night Shooting

Wild pigs are generally active at dusk and dawn, but human activeness and climatic conditions may cause them to exhibit nocturnal feeding behaviors across portions of their range. In these areas it may be virtually efficient for hunters to shoot pigs at nighttime under the cover of darkness. Dark vision optics and the contempo increment in use of sound suppressed rifles has profoundly enhanced the success of this method (5). Using this blazon of equipment allows individuals to remove big portions of wild sus scrofa populations, whole sounders in some cases, at ane fourth dimension in big open terrain. Night shooting is highly constructive in agricultural fields, only its efficacy as well declines as vegetation density increases and wild hog density decreases (56). The all-time prescription for this method of population reduction is likely in agronomical areas reporting loftier levels of damage from wild pigs, in conjunction with other large-scale population control methods.

Recreational Hunting

Recreational hunting of wild pigs is common in the U.s.a. (56). In fact, wild pigs are considered a desirable species in some of these states for both "bays" and meat (79). Recreational hunting can occur in the class of stalking or hunting over baited areas, and as with the other forms of control, has the limited potential be effective in reducing localized populations of wild pigs in areas of high density (5, 56). Increased homo activity associated with control measures can influence the behavior of wild pigs and recreational hunting has been shown to increment the dispersal of wild squealer populations. In addition, selective harvest of only large males as "trophy" animals can also be counterproductive in population reduction efforts. Removal of females and juveniles have the greatest bear upon on lowering production of the population, thus, choosing not to harvest that portion of the population in favor of males is much less effective than indiscriminate harvesting across all sexual activity and historic period classes (80).

Some states which historically did not let recreational hunting of wild pigs have established statewide hunting programs in an attempt to solicit assistance from the public in decision-making wild pig populations. Even though the intentions were good, these statewide hunting programs accept sometimes resulted in population increases and rapid range expansions (15, 83, 84). Popularity of wild pigs as a game species coupled with economic incentives generated by trophy hunting industries has resulted in the human-mediated transportation of wild pigs (illegal in Texas) to areas previously not populated past wild pigs (84-86). For example, Tennessee implemented a statewide hunting program in 1999, and by 2011 wild hog populations expanded from 6 to 70 counties (84). Similarly, in 1956 when wild pigs were designated a game animal in California, their range was limited to merely a few coastal counties. By 1999, nevertheless, they had spread to 56 of the state'southward 58 counties (83, 85). One scientific study besides stated that the financial incentives associated with the wild pig hunting industry directly led to the intentional transportation and release of wild pigs on private properties, and that anyone who argues that hunting wild pigs is an effective means of reducing their population is ignoring the power of such incentives to private landowners (83).

Bounty Programs

To overcome the challenges of selective harvest by recreational hunters, some local governments have implemented compensation programs to incentivize hunters in an effort to increase hunting pressure level in sure areas. These efforts are often futile and have failed to increase hunting pressure significantly. Further, some studies have shown that bounty programs actually event in an increment in wild hog populations due to the use of supplemental feed equally bait and selective "trophy" hunting (80, 81). In addition, these programs oftentimes incentivize fraud or farming for bounties. Bounty programs are typically implemented at the county level and provide financial rewards for the harvest of animals within canton boundaries. When the financial reward is perceived to outweigh the chance of penalty, unscrupulous people volition plow in animals harvested outside those county boundaries as part of the bounty program. This type of fraud can profoundly reduce the already low price efficacy of bounty programs (80, 82). In addition, when there is an economic incentive to harbor an invasive exotic species for hereafter gain, it may go increasingly difficult to remove that species. If an private can economically profit from the harvest of wild pigs, there is an incentive to get out portions of the population on the landscape and in some cases, raise them for future profit (82).

Closing

Wild hog populations in the Us crusade irreversible ecological damage and accept an enormous economic impact. The extent of these economical damages are highly correlated with population size and density (14, 45). Population models indicate that the wild pig population size and range will continue to grow if left unchecked; thus, damages from wild pigs will also increase (11, 12, 14). Information technology is estimated that annual population control efforts would demand to continuously achieve 66-70% population reduction just to hold the wild pig population at its electric current level (14, 28). Estimates from Texas indicate that with current command methods, however, annual population reduction merely reaches approximately 29% (fourteen). The demand for novel methods of wild grunter population control is obvious.

Additional Resource

- A Landowner's Guide to Wild Pig Management – Practical methods for wild pig control PDF

- Feral Swine-Managing an Invasive Species

- Feral Swine and Ungulate Impacts Research

References

For the complete list of cited references, please download the publication:

- Environmental and Direction of Wild Pigs (PDF)

- Ecologia Y Manejo de Cerdos Ferales (PDF)

penningtonmari1948.blogspot.com

Source: https://tpwd.texas.gov/huntwild/wild/nuisance/feral_hogs/

0 Response to "I May Be Wild but I m Not What Was That Third Thing Again"

Post a Comment